The rise of the Internet of Things threatens collective cybersecurity and confuses citizens, concerned about their individual privacy

Reality and fiction are the concerns of citizens regarding their online privacy. In 2018 the webcam scam has returned, with which some computer hackers tried to extort several readers of the magazine The Register: an anonymous email asked them several thousand dollars (in bitcoins) to keep secret a video that allegedly they had recorded them from their own webcam while enjoying pornographic material on their computer. As presumptive evidence of the intrusion, the scammers presented each user with a real password, which they used to access a forum that they had hacked.

Alerted by a skeptical victim, the security experts of the British publication recommended to all its readers to ignore this type of emails: “Do not panic, do not pay. It is very unlikely that this video exists. Change your password and consider using double-factor authentication and a password manager to keep your accounts secure. ” The incident showed Internet users accustomed to using weak passwords, and at the same time worried about an assault on their privacy similar to that suffered by the protagonist of a chapter of the science fiction series Black Mirror, in its third season.

The truth is that technically it is possible. Also last summer, researchers from the computer security company ESET divulged the discovery of InvisiMole, a new and powerful malware that has been in circulation since 2013 and precisely does that: it camouflages itself as a file of the Windows system and, among other things, takes control of the user’s webcam and microphone, to observe their activities and to collect personal information and documents. Zuzana Hromcová, an ESET analyst, explains that this program had remained under the antivirus’s radar because “it uses several techniques to avoid detection and because it has only been used against a small number of highly chosen victims, in Russia and Ukraine.”

InvisiMole is a cyber-espionage tool like the one that has been used by the FBI for years, according to Marcus Thomas, former deputy director of the Technological Operations Division of the US federal agency. Also in 2013 a study by Johns Hopkins University showed that it is possible to infect a computer and record with your webcam without turning on the light that alerts the user, and researchers detailed in their article how to do it on a variety of Apple computers.

If Mark Zuckerberg does it…

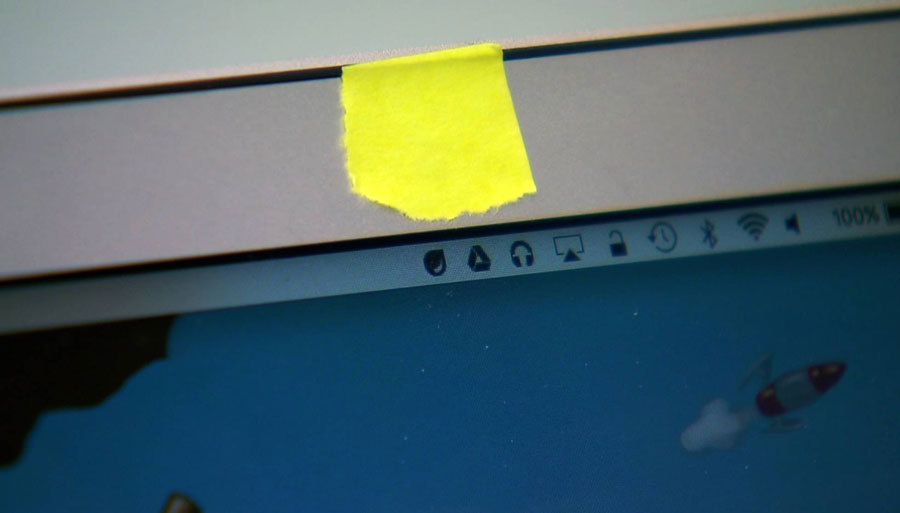

Being spied on with the webcam itself is a possibility that goes beyond online scams and television series, and the global murmur that generated the photo in which you see the very Mark Zuckerberg, president of Facebook, with the camera of his laptop covered with a tape.

Covering the web cameras is an increasingly widespread practice, both in computers for personal use and at work. And there is also widespread suspicion towards intelligent speakers – like those that Amazon and Apple are debuting these days in Spain – especially after last August was unveiled at the DEF global hacker conference with a trick to convert an Amazon Echo speaker. in a spy microphone. In the last year, smart loudspeakers have become the most popular device of the so-called Internet of Things, a technological category destined to grow 300% over the next few years.

Thus, the latest awareness campaign of the REIsearch project of the European Commission states that by 2025 the number of connected objects will have grown to 75,000 million, including a variety of personal devices such as cars, pacemakers or toys; also to household appliances, light bulbs or plugs; and to sensors and machinery for public infrastructures such as hospitals, power plants or transport networks.

Smart objects, the great objective of the ‘hackers’

For hackers, all those connected objects are much more appealing than our webcams, according to the renowned cybersecurity analyst Mikko Hypponen: “People may think: Why would someone want to hack into my fridge, microwave or smart coffee machine? The motivation is usually not to manipulate the device and spy on it, but to gain access to our network and passwords. The weakest link in our networks are not our computers or mobile phones, they are our connected objects, “Hypponen explained at a conference in Dublin last week. “If a device is described as” intelligent “, that means it is vulnerable,” recalls the expert in each of his interventions.

That threat became a reality when, two years ago, the Mirai attack knocked down the Amazon, Spotify, Twitter and Netflix web servers, as well as the New York Times page. These and other 150,000 websites were inaccessible for hours, because there were many visits at the same time. But behind those visits there were no people, but objects connected to the Internet (televisions, refrigerators, security cameras) that had been infected and followed the orders of a malware, which recruited them to form an army or network of computer botnets (botnet) . It was the first massive cyberattack starring the Internet of things.

The latest Europol report on organized crime on the Internet highlights the fear that the next major attack of this kind may cause a global paralysis of the Internet. And he also points out as a great concern the persistent threat of ransomware, the malicious programs that ask for a ransom to unblock the computer system they have infected. One of them, Wanna cry, prevented in 2017 that thousands and thousands of people could access basic services such as electricity (in Spain) and health (in the United Kingdom).

How to protect yourself?

In cases like the latter the Internet of Things was the victim of the attack, and not the transmitter. And that calls into question the use of “smart” health devices, which, when connected to the Internet, can be taken hostage in an attack like Wannacry, and thus put at risk the lives of patients who depend on its functioning. .

In this context California has just approved the first law on the security of smart objects, which imposes on all manufacturers new security measures (and not just privacy) from January 1, 2020.

Meanwhile, experts ask users to be demanding with the security of the connected devices installed in their homes, to keep the software of all their computers updated, to use password managers and to strengthen the security of their home networks. Four tips to address these large-scale threats to collective cybersecurity … and also much more useful than a tape on the webcam, if the goal is to protect the privacy of very infrequent intrusions-outside the world of espionage and people like Zuckerberg whose secrets are worth many millions of dollars. For the common Internet user, the risk of covering the webcam is to have a false sense of security and remain oblivious to the new threats of the Internet of Things era.